Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Kaczinski’s Resignation

- 3. Appointment of Matthew Schwarz and the Defective Notice

- 4. Facebook Disputes and the Sheriff’s Press Release

- 5. Supervisor Stancil’s Lawsuit Against Sheriff Barnes

- 6. Locked out of Office

- 7. Warrants, Seizures, and Judge Relph’s Ruling

- 8. The Amended Lawsuit

- 9. The GOP Nominating Convention and Brant’s Path Forward

- 10. The Special Election and Its Outcome

- 11. Special Election Costs: Facts vs. Spin

- 12. Beyond Madison County

- Timeline of Events

1. Introduction

Madison County has been in political turmoil for months. While the tensions have been brewing for years, they ramped up in 2025 and reached a boiling point this past summer. What follows is a retrospective look at what unfolded, not as a soundbite on the evening news or a Facebook post or letter to the editor but as a single story stitched together. While much has happened both before and after the summer of 2025, this article is focused on the resignation of Auditor Kaczinski, the appointment of Auditor Schwarz, the election of Auditor Brant, and the controversy surrounding these events.

While most in Madison County want to put these events behind them, the truth still matters and much of what is shared in this article has not been shared publicly until now, certainly not in one article. Much of the reporting by other local news outlets has been inaccurate. We have taken great care to source the facts stated in this article so you can view the source documents yourself and draw your own conclusions.

Madison County is just one county out of thousands; however, it represents what many are seeing across the country… opposing worldviews on how we should be governed and even what is considered appropriate and civil discourse in America.

2. Kaczinski’s Resignation

While this story could have many starting points, The Madison Report begins this chapter of the story on May 6, 2025, when Madison County Auditor Teri Kaczinski announced she was resigning after only being in office since January. Her resignation would take effect on July 4. Kaczinski’s letter of resignation said, in part:

“When I was sworn into office, there was no transition plan in place and the office was in disarray. Still, I embraced the challenge with the support of a capable staff who knew the operations well. We rolled up our sleeves and got to work.

What I did not anticipate was the relentless online harassment, inaccurate and slanted media coverage, bureaucratic harassment by both the media and a small group of people intent on grinding this office to a halt, and the toxic social media environment that deterred qualified applicants and undermined staff morale. The barrage of misinformation, false accusations, and personal attacks has made it nearly impossible to focus on the work the public entrusted me to do.

Perhaps most disheartening is that these attacks have extended to my staff—dedicated public servants who do not deserve to work under such hostility. I cannot in good conscience allow them to continue to bear this burden.”

Although not mentioned in Kaczinski’s letter of resignation, one issue that drew attention during Kaczinski’s time in office was an investigation initiated by Sheriff Jason Barnes. On April 1, Barnes responded to an email from Katie Kaplan at WHO13 who asked him if he would confirm whether there was an investigation into Supervisor Heather Stancil, her connections with Craig Bergman and whether the information had been forwarded to Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation (DCI). Craig Bergman was a consultant hired by Kaczinski in January 2025. Kaplan also asked the Sheriff if he was “investigating if any of the elections software or other digital records owned by the county have been tampered with.”

Barnes responded to Kaplan:

“Yes, numerous residents have made complaints to this office in regard to Bergman, the Board of Supervisors, the Madison County Auditor, and the consulting contract.

Due to the nature of the complaint and the officials they pertain to, we will be forwarding the complaint to Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation who will handle the investigation.

I am unaware of who has had access to our voting equipment or it’s software. But I do know that is a concern for many residents and is included in the original complaint.”

Shortly after Barnes’ response to Kaplan on April 1, WHO13 aired a story on their nightly broadcast where anchor Andy Fales incorrectly opened Kaplan’s story by saying the Madison County Auditor was charged with fraud. However, Auditor Kaczinski was never charged with fraud. WHO13 was conflating two different elected officials and different issues. The video containing the error was posted on the WHO13 website along with a print article and then removed a short time later.

News of the referral to DCI and misleading reporting intensified scrutiny of the Auditor’s Office and became a prominent subject in local news coverage. That scrutiny continued until August 1, when the Warren County Attorney’s Office announced the conclusion of the investigation. After months of review with both the Warren County Attorney’s Office and the DCI, prosecutors determined there was insufficient evidence to bring charges.

By the time that announcement was made, however, Kaczinski had already stepped down. The investigation’s duration and the publicity surrounding it had become part of the broader series of challenges that defined her tenure. At the time, it was on the minds of Madison County residents who were left to wonder what would be uncovered. In the end, the case was quietly closed.

Following the dismissal of the case, The Madison Report asked Kaczinski in an email if she stepped down due to the DCI investigation. She rejected that assertion, stating:

“It was quite the opposite. I was fully confident that there had been no breach of security related to election equipment, and I did not want my resignation to be misconstrued as an admission of any wrongdoing. However, as I explained in my resignation letter, the circumstances had become unsustainable.

The ongoing pressure, misinformation, and public scrutiny extended well beyond the professional sphere and began to significantly impact my family. The strain of the situation created a constant atmosphere of stress and anxiety in our household. What should have remained a professional challenge became a deeply personal burden, affecting the health, stability, and well-being of those closest to me.

Ultimately, I determined that continuing in the role was no longer compatible with safeguarding my family’s emotional and psychological welfare. It was an extremely difficult decision, but a necessary one.”

3. Appointment of Schwarz and the Defective Notice

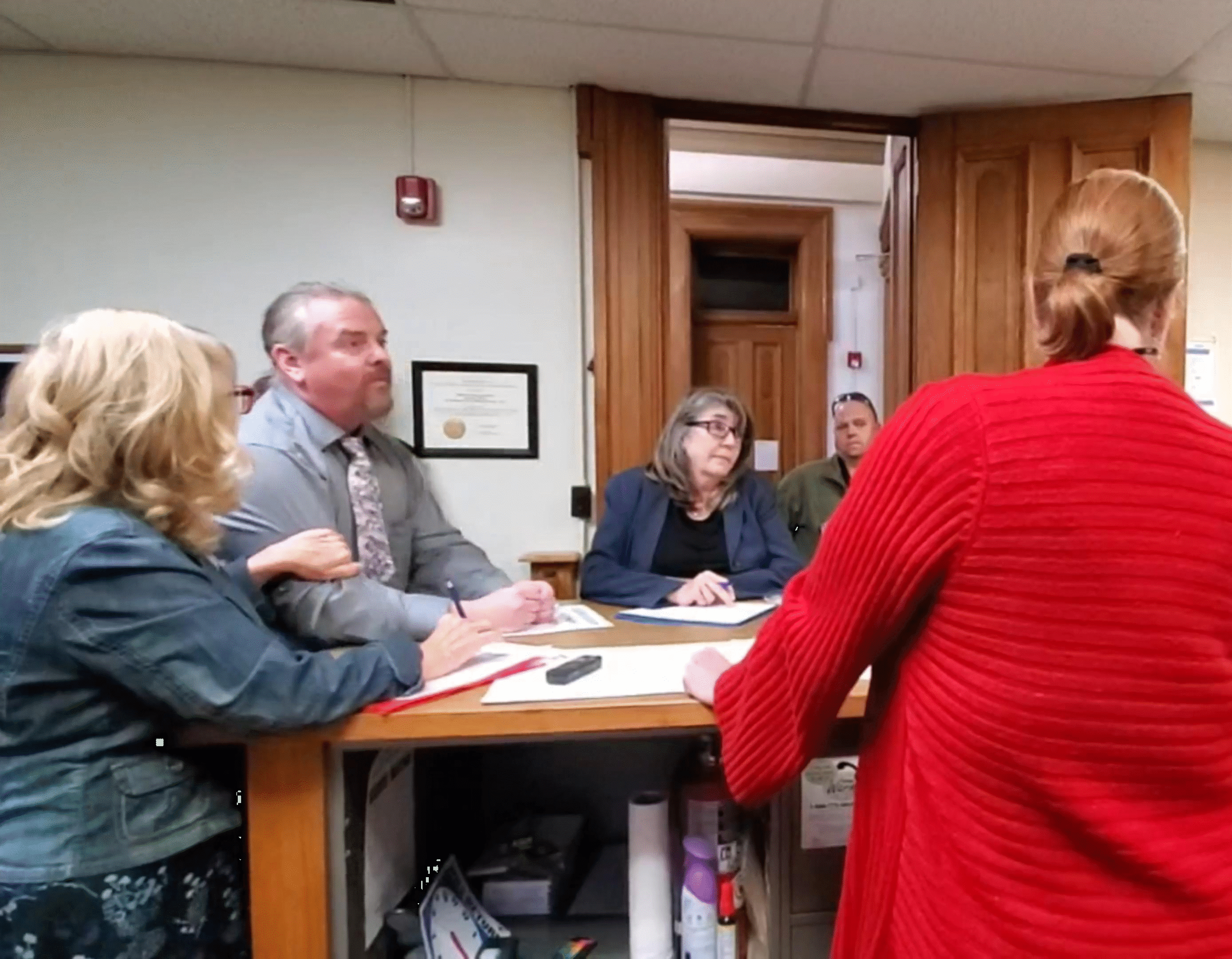

Following Kaczinski’s letter of resignation in May, the Board of Supervisors decided to appoint a successor rather than call for a special election. On May 28, 2025, the county posted a notice announcing that applications were being accepted for the position of Auditor. Matthew Schwarz was selected as Auditor in a 2 to 1 vote by the Board of Supervisors on July 3 and sworn in on July 7. But the job notice was defective: it failed to include required language informing citizens of their right to petition for a special election, and no subsequent notice with the correct language was issued by the Board Clerk/Elections Deputy before the appointment on July 3.

4. Facebook Dispute and the Sheriff’s Press Release

The defective notice apparently went unnoticed in the short term. In the meantime, a controversary was brewing between Supervisor Heather Stancil and Sheriff Jason Barnes. It started on July 9 with a Facebook post by Stancil. She shared a statement from the Auditor’s Office at the request of the newly appointed Auditor Matthew Schwarz, who did not maintain a Facebook page. Schwarz was responding to some questions he had been receiving from the public. The post made on behalf of Schwarz was not related to a special election however the online comments soon turned to that topic.

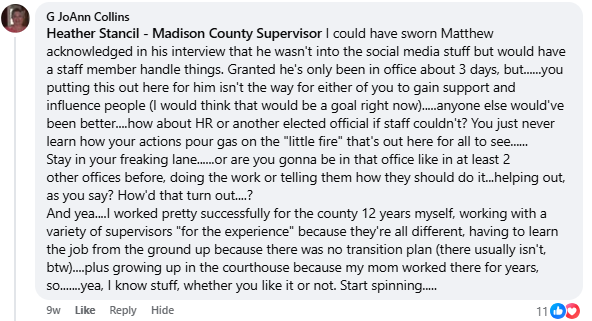

In one comment on the post, former County Treasurer Joann Collins criticized Stancil for posting on Schwarz’s behalf and accused her of overstepping her role. Her comment:

Former Treasurer Collins is currently the Chair of the Madison County Civic Alliance – Iowa, a registered PAC in Iowa. This organization also has a Facebook page by the same name which regularly criticized Teri Kaczinski, Supervisor Heather Stancil and Matthew Schwarz.

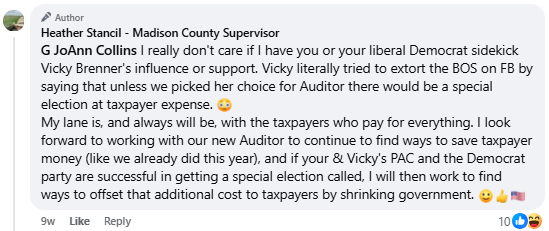

In response to Collins, Stancil commented:

The following day, Winterset City Councilman Mike Fletcher responded to that comment, accusing Stancil of threatening to fire county employees to pay for the election. He labeled her remark intimidation and a violation of constitutional rights.

Stancil responded by clarifying that the election would create costs that had to be covered either by raising taxes or cutting elsewhere, writing: “There is no magical money tree growing on the Courthouse lawn.”

On July 14, Sheriff Jason Barnes escalated the dispute by issuing an email press release to several local news outlets stating that Stancil’s “statement and a preliminary investigation have been forwarded to the Iowa Attorney General’s Office as Iowa law requires.” This resulted in numerous news stories being generated in the area.

5. Supervisor Stancil’s Lawsuit Against Sheriff Barnes

Two days later, on July 16, Stancil countered by filing a federal civil rights lawsuit against Barnes, alleging retaliation against her constitutionally protected political speech. The complaint described Barnes’ action as “extraordinary,” arguing that he “absurdly called this benign statement about the need for balanced budgets a felonious act of voter intimidation.” It further stated: “No reasonable law enforcement officer could find an elected official’s statement about offsetting unexpected expenses for a special election to constitute an act that ‘intimidates, threatens, or coerces.’ Taking a statute designed to prevent…standing in front of a polling place and threatening violence…and applying it to a public official stressing the importance of balanced budgets is preposterous.”

The lawsuit also underscored First Amendment protections, noting: “Stancil, as both a citizen and an elected official, has a right protected by the First Amendment to communicate her views on policy matters without fear of sanction from the government.”

The episode drew strong reactions in Madison County. Supporters of Barnes defended his actions as protecting election integrity, while critics described the move as a misuse of law enforcement authority against an elected County Supervisor. The lawsuit is currently pending.

6. Locked Out of Office

That same week, the defective notice issue was ramping up at the courthouse.

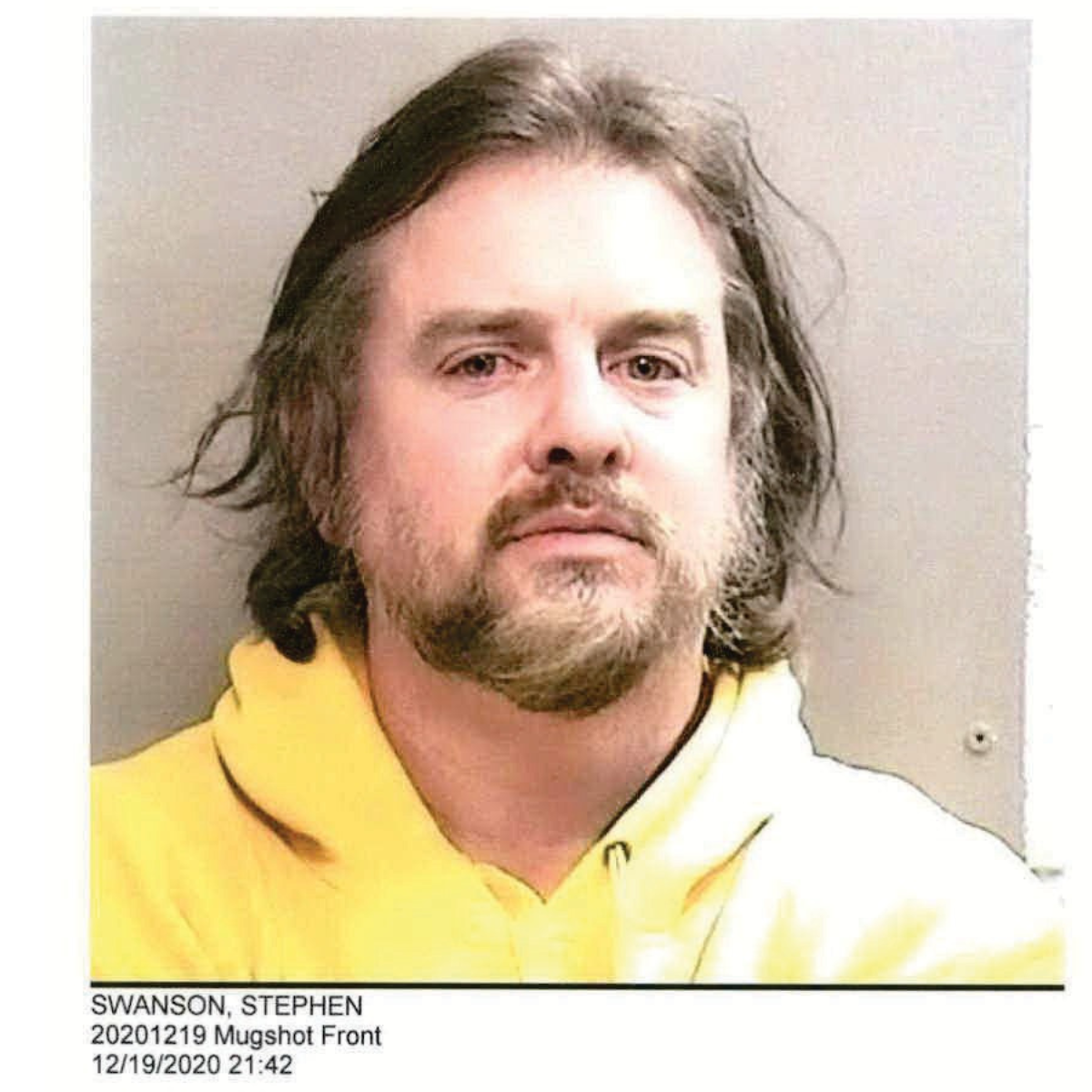

On July 14, County Attorney Stephen Swanson emailed Supervisor Heather Stancil regarding the defective May 28 appointment notice. He wrote: “Looks to me since you left off the language council need to repost. Theoretically someone could challenge based on improper notice.” As a result, the notice was reposted with the proper legal language. On July 16, Swanson sent an email to Auditor Schwarz, Acting Treasurer Kylee Barber, and the Board of Supervisors, copying in Sheriff Barnes and the Auditor’s Office staff:

“After consultation with the Secretary of State’s and the Iowa Attorney General’s Office, and due to the Notice posted yesterday noticing that there is a vacancy in the office of the Madison County Auditor, it is the opinion of this office that at this time, Matthew Schwarz was not appropriately appointed as Madison County Auditor, that the position remains vacant until filled on July 22, 2025 upon vote by the Board of Supervisors. Per Iowa Code 69.3, with no appointed Auditor, and with no temporary appointment, the Possession of the Auditor’s office is to be held by the County Treasurer until such time that an Auditor can be appointed. Following this notice all individuals not formally employed by the Madison County Auditor’s Office shall vacate the premise, relinquish county property, and return their keys to Lawra Mathes (first deputy auditor).”

Schwarz responded 23 minutes later with an email stating:

“Hi Steven

Iowa Code § 69.2(2) provides the process for determination if a vacancy exists in a county office. That code section states that the entity responsible for making an appointment to fill a vacancy in an office has the authority to determine if a vacancy exists. You are not the entity with this responsibility, that is the Madison County Board of Supervisors. Even if you were the entity, there is a procedure in place in that code section for due process to evaluate whether the vacancy exists or not. No one had the authority to circumvent those procedures.”

According to Schwarz, he left the office under duress and threat of arrest shortly thereafter. Supervisor Stancil was at the courthouse at the time also. According to Stancil, Swanson told her that Schwarz couldn’t be in the office because he was not the Auditor and he needed to leave. Stancil also told The Madison Report that when she went into the Auditor’s Office to speak with Schwarz, she was stopped by Elections Deputy Mikayla Simpson (Garside) and told that per the county attorney, only employees of the Auditor’s Office were authorized to be there and Schwarz needed to leave or he would be trespassed and arrested. A text from Simpson the next morning confirmed that Simpson was under the impression that Schwarz could be “trespassed from the courthouse” if he came into the office.

As a result of Swanson’s directive, for nearly six days Schwarz was locked out of the role he had been appointed to fill. Then, at the July 22 Board of Supervisors meeting, Swanson stated that Schwarz was the County Auditor. No clear explanation was offered for the reversal, however had the office been vacant when the citizen petition for a special election was filed, the petition itself could have been challenged as invalid.

In fact, that morning, on July 22, Madison County resident Marisa Schneider filed an objection, telling The Madison Report: “I was convinced, along with several others, that there was no Auditor on the day the petition was submitted.” Schneider argued the petition was “untimely and legally insufficient.” On July 28, Schneider’s objection was dismissed and the petition was certified.

Many residents were frustrated in the July 22 Board of Supervisors meeting that Stancil was repeatedly asking Swanson if Schwarz was the Auditor or not. The Madison Report asked Stancil for a reason for this insistence that Swanson answer the question. She gave two reasons for her need for clarity:

- Swanson’s answer would determine if the petition was valid. If Schwarz was being appointed that day, the petition could be challenged as invalid and residents would need to re-do the signatures. Signatures must be dated AFTER the appointment. The board had on the agenda to appoint Schwarz on July 22; however, the petition was turned in on July 17.

- Stancil received tips from multiple sources that Sheriff Barnes and County Attorney Swanson were prepared to arrest Stancil that day for election interference if she voted to pass the resolution to appoint Schwarz. Re-appointing Schwarz was being seen as trying to invalidate the signatures. Alan Ostergren, Stancil’s attorney, was present at the July 22 meeting in the event that Stancil was arrested and to provide legal counsel if needed.

Whether Stancil would have been arrested is unknown, however the information she received was credible enough to her and her attorney to warrant some clarity prior to moving forward with the resolution to appoint.

As mentioned earlier, Swanson reversed course, stating that the office was not vacant and Matthew Schwarz was the County Auditor. This meant the resolution to appoint was no longer needed. Even though Swanson’s July 16 directive had vacated the office, once he stated that Schwarz was Auditor, it was treated as if the six-day removal had never occurred. It obviously did occur and it negatively impacted the Auditor’s Office’s ability to serve the county.

Later in the meeting, Schwarz gave a 30-minute presentation on several items of concern in the Auditor’s office that he wanted to fix. He went back to his office following the meeting as the Auditor, but not before verifying that he could return without being arrested.

7. Warrants, Seizures, and Judge Relph’s Ruling

In the midst of the six-day uncertainty of whether Madison County had an Auditor, both Auditor Matthew Schwarz and Supervisor Heather Stancil had warrants served against them to seize property. On Friday evening, July 18, 2025, Madison County deputies executed search warrants at the homes of Schwarz and Stancil.

The warrants authorized the seizure of their personal cell phones and county laptops. Deputies seized both officials’ personal phones at their homes. Stancil also lost access to her county-issued laptop, which she had been using daily as Board Chair. Schwarz’s county laptop, however, was still at the courthouse and was later seized from his desk.

The applications for those warrants rested largely on information provided by Elections Deputy Mikayla Simpson (Garside), who alleged that both Schwarz and Stancil were attempting to alter appointment dates and deadlines in order to delay the special election. Sheriff’s Deputy Donald Kinney applied for and executed the warrants at the homes of both Stancil and Schwarz. Sheriff Jason Barnes and County Attorney Stephen Swanson were involved in the process that led to the warrants being signed by District Court Judge Thomas P. Murphy.

The timing of the search warrants was notable. Not only were the warrants executed only two days after Stancil’s lawsuit and Schwarz’s eviction from his office, executing the warrants late on a Friday meant that normal avenues for contesting or limiting the seizures were effectively closed for several days. It left two top county officials suddenly without their phones heading into the weekend, disrupting both their personal and official communication.

On July 31, Madison County District Judge Dustria Ann Relph ruled that the warrants used to seize the personal cell phones of Auditor Matthew Schwarz and Supervisor Heather Stancil lacked probable cause and must be quashed.

Relph’s decision was highly unusual. In Iowa, it is rare for a search warrant to be overturned after being signed by a judge, and rarer still for two to be thrown out in the same case. The motions to quash were filed by attorneys Alan Ostergren, representing Stancil, and Alex Gilmore, representing Schwarz, who joined in the arguments. They contended that the warrants had been based on flawed applications and did not meet the constitutional requirement of probable cause.

The applications, presented by Deputy Donald Kinney and advanced with the involvement of Sheriff Jason Barnes and County Attorney Stephen Swanson, relied almost entirely on the statement of Elections Deputy Mikayla Simpson. Simpson alleged that Schwarz and Stancil were attempting to alter election timelines.

However, according to court transcripts, the judge found that the affidavits failed to establish exactly what law Stancil and Schwarz were allegedly breaking, or a direct link between the alleged conduct and the contents of the officials’ personal devices. The judge stated that “the application does not give the Court any indication that what was done was illegal or for nefarious purposes.” She later stated, “I find the general heading ‘election misconduct’ is not specific enough, as there is actually no offense called…election misconduct.’ If you look down into the body of [Iowa Code] 39A, again, there is registration fraud, vote fraud, duress, bribery, conspiracy. Those would be specific offenses. So for these reasons, the warrant is quashed due to lack of probable cause.”

The ruling returned both Schwarz’s and Stancil’s personal phones. Their county-issued laptops, however, were not included in the motions to quash because those are county property and not subject to Fourth Amendment protections. Stancil continued to work on alternate devices until September 4, when her laptop was returned. Schwarz’s county laptop was never returned during his time in office, and was allegedly returned to the new County Auditor on September 4.

The quashing of the warrants raised questions about the roles of Sheriff Barnes and County Attorney Swanson, and the real reasons for seeking the warrants. Both had a role in the process, and the court’s ruling underscored the unconstitutionality in their approach. Critics said the rare rebuke from Judge Relph highlighted how far county law enforcement had overreached in pursuing the case.

The warrants and seizures added to the public uncertainty. Having both the county’s Auditor and the Chair of its Board of Supervisors under criminal investigation at the same time was without precedent in Madison County. For many residents, the sight of deputies seizing personal property from two elected officials highlighted the divisions in county politics.

8. The Amended Lawsuit

Following the ruling by Judge Relph, Supervisor Heather Stancil amended her lawsuit to include County Attorney Stephen Swanson, Deputy Sheriff Donald Kinney, and Elections Deputy Mikayla Simpson (Garside), in addition to Sheriff Jason Barnes who was already named. Auditor Matthew Schwarz joined Stancil in the lawsuit against Swanson, Kinney, Simpson, and Barnes.

The amended lawsuit, filed August 4, alleges that county officials retaliated against Stancil and Schwarz for exercising their constitutional rights. It claims the press release, criminal referral, and search warrants were used to punish protected political speech and association. The lawsuit also argues that the warrants — which Judge Relph had already ruled legally defective, lacked probable cause, and must be quashed — violated their Fourth Amendment rights because they were based on incomplete or misleading information provided to the court.

The lawsuit states, “Taken together, the acts of Barnes, Swanson, Kinney, and Simpson demonstrate a coordinated campaign to remove, silence, and discredit elected officials who challenged their authority.”

The suit seeks damages, legal fees, and a jury trial. The case is still pending.

9. GOP Nominating Convention and Brant’s Path Forward

While the courthouse was consumed with legal battles, preparations for the special election were also moving forward. The Republican Party chose to nominate a candidate to be placed on the ballot, which required reconvening the GOP county delegates selected in 2024. The convention took place on July 28.

At the convention, delegates chose Matthew Schwarz for Auditor by unanimous consent since he was the only person nominated. Attention quickly turned to whether Michele Brant had been unfairly blocked from consideration or whether, as party leaders argued, she was simply never placed into nomination.

To add fuel to the fire, on August 12, The Winterset Madisonian published a letter from former Madison County Republican Central Committee (MCRCC) member Frank Santana, who sharply criticized the handling of the GOP nominating convention. Santana alleged that Brant, though a registered Republican, was denied the opportunity to address delegates and seek their support. Her request, he wrote, “was denied by the Chairman of the MCRCC, against the policy and procedures put in place,” which he described as “a dereliction in duty, obligation and disservice to Madison County Republican voters.”

Santana’s letter quickly dialed up the rhetoric. Supporters of Brant echoed Santana’s claim that party leadership had blocked her path, while others argued the accusation misrepresented the convention process.

In response, Ken Luckinbill, chair of the MCRCC at the time, submitted a rebuttal letter to The Madisonian, which was rejected. It was then posted on the Madison County Republican’s Facebook page. Luckinbill stressed that the convention was controlled by the delegates themselves, not the Chair, and that any nominations had to come from the floor. Brant, he noted, was not placed into nomination by any of the delegates.

Leslie Beck, co-chair of the MCRCC at the time, assisted with the convention and confirmed that all delegates were contacted to ensure participation.

When asked why Brant was not nominated, Beck said: “I was fully expecting her to be nominated. In hindsight though, Brant and her supporters may not have wanted her to be nominated and risk losing the nomination. She had a better chance as an Independent and that proved to work well for her.” While Santana framed the issue as leadership silencing a candidate, Luckinbill and Beck countered that the outcome reflected both the open opportunity for nominations and the delegates’ silence. In the weeks that followed, the debate over Brant’s candidacy spilled into public forums, Facebook posts, and additional letters to the editor, keeping the dispute alive leading up to the Special Election.

10. The Special Election and Its Outcome

On August 26, just 35 days after the certification of the petition for a special election, Madison County voters went to the polls to decide who would serve as County Auditor.

The race pitted appointed Auditor Schwarz as the GOP candidate against Independent candidate Michele Brant, who had previously run as a Democrat for county supervisor in 2020. Brant also had additional Democrat ties despite telling WHO13 that she was a life-long Republican. Many of her donors were Democrats and she used a fundraising platform with ties to the DNC and progressive organizations.

When the votes were counted, Brant prevailed. Her victory came after a summer filled with disputes over notice errors, lawsuits, search warrants, and a wave of commentary in newspapers and online.

Despite the county being a Republican stronghold, confusion and controversy contributed to Brant’s win. Throughout the campaign, Brant’s most vocal supporters framed Schwarz as a political ally of Supervisor Heather Stancil — who herself had filed a lawsuit against Sheriff Jason Barnes for violation of her constitutional rights. Then when warrants were served against both Stancil and Schwarz on the same night, that further linked the two in the minds of voters. Both Schwarz and Stancil stated their first meeting had been during his Auditor interview. We have not been able to find any evidence that they knew each other prior to Schwarz’s June 30 public Auditor interview.

The portrayal of Schwarz as a “Stancil pick” resonated with voters loyal to Barnes, reinforcing the belief that supporting Brant was a way to push back against Supervisor Stancil. The complexity of the legal disputes, combined with swirling accusations and incomplete information, left many residents uncertain about what had actually transpired in county government.

Against that backdrop, Brant’s campaign emphasized a simpler message: she would “calm things down.” While critics questioned her qualifications and political affiliations, voters responded to the appeal for stability after a turbulent year in the county. With the political climate in Madison County, it was doubtful that anyone could fulfill a campaign promise for calm in Madison County.

11. Special Election Costs: Facts vs. Spin

The cost of the election was a hot button issue in Madison County. In July, both Supervisor Stancil and Supervisor Hobbs were indicating a possible cost of $50,000. Supervisor Hobbs stated on July 4 that “according to the Elections Deputy, a recent Warren County special election cost $75,000, Madison County has approximately 2/3 the # of voters as Warren.”

According to county records, the Special Election costs totaled just under $18,000. The Madison Report asked Stancil why the original estimate was so far off. Stancil explained that the higher estimate came from initial conversations with Simpson and were based on special election costs in Warren County. Cost-saving measures—like reducing the number of polling sites and allowing voters to vote at any site – were later implemented.

Why does this matter now? Months after Stancil and Hobbs made those statements, WHO13’s Katie Kaplan reported on the inaccurate estimate that Stancil gave. However, the context is missing. Why were the Supervisors so off the mark in their estimates? It appears that they were going off of the information they had at the time, including what was provided by the Elections Deputy Simpson. Months later, to hold someone to a statement made prior to new information being obtained is disingenuous. Also, missing from Kaplan’s story was the total cost of the election since more than $4800 in election expenses had not been paid at the time of her September story. We will give Kaplan the benefit of the doubt that Simpson did not inform Kaplan of the additional expenses that had not been paid yet. Television, print newspapers, and the internet can be powerful tools in politics. In a moral and civil society, they provide valuable information to the electorate. However, when these platforms are used to twist the truth, they can do irreparable damage to those in the crosshairs.

12. Beyond Madison County

What happened in Madison County is not unique. From rural towns to major cities, citizens are grappling with contested elections, political polarization, and the role of law enforcement in politics. Madison County’s fight over the Auditor’s Office illustrates how local disputes reflect deeper national divides — and why the way we resolve them matters.

Timeline of Key Events (all dates are in 2025)

April 1 – Sheriff Jason Barnes responded to Kaplan’s email regarding the Auditor’s Office which prompted WHO13’s story on Auditor Kaczinski.

May 6 – Auditor Kaczinski announced resignation, effective July 4.

May 28 – County posted notice for Auditor applications — post was later found to be defective.

July 3 – Board of Supervisors voted 2–1 to appoint Matthew Schwarz as County Auditor.

July 7 – Schwarz sworn in as Auditor.

July 9– Supervisor Heather Stancil posted statement on Facebook for Auditor Schwarz, sparking public criticism and controversy.

July 14 – Sheriff Barnes issued press release email regarding Stancil’s Facebook comments and his referral to the Iowa Attorney General.

July 14 – County Attorney Stephen Swanson advised Supervisor Stancil regarding defective May 28 notice.

July 16 – Notice reposted, emails exchanged regarding vacancy issue and Schwarz forced out of office for 6 days.

July 16 – Stancil filed federal civil rights lawsuit against Barnes.

July 18 – Deputies executed search warrants at the homes of Schwarz and Stancil, seizing their personal cell phones (and Stancil’s county laptop).

July 22 – Swanson reversed course and recognized Schwarz as Auditor again. Petition objection filed the same morning by resident Marisa Schneider.

July 28 – Objection hearing held; petition certified and special election moved forward. GOP convention also held — delegates nominated Schwarz.

July 31 – District Judge Relph ruled search warrants defective and quashed them.

August 1 – Warren County Attorney announced closure of DCI investigation initiated by Barnes around April 1. The case was dismissed with no charges filed.

August 4 – Supervisor Heather Stancil amended lawsuit to add County Attorney Swanson, Deputy Sheriff Kinney, and Elections Deputy Simpson (Garside). Auditor Schwarz joined the lawsuit.

August 12 – Letter from former GOP committee member Frank Santana published in The Winterset Madisonian, criticizing party leadership.

August 20 – Rebuttal to Santana by Ken Luckinbill posted on Facebook.

August 26, 2025 – Special election held. Michele Brant defeated Matthew Schwarz.

Author’s Note

This article was written with a commitment to transparency, accountability, and the public’s right to know how local government operates. Facts and quotes are based on public records, court transcripts, and firsthand sources. Opinions are that of The Madison Report editorial staff and authors. The intent is not to stir up division, but to ensure citizens can make informed judgments about the actions of those entrusted with public authority.

Free speech and open discourse are essential to preserving our Constitutional Republic. The ability to question, to disagree, to state our opinions, and to hold government accountable without fear of retaliation is not only a right — it is a duty shared by every citizen. That principle guides this reporting and underscores why these events matter far beyond one county.